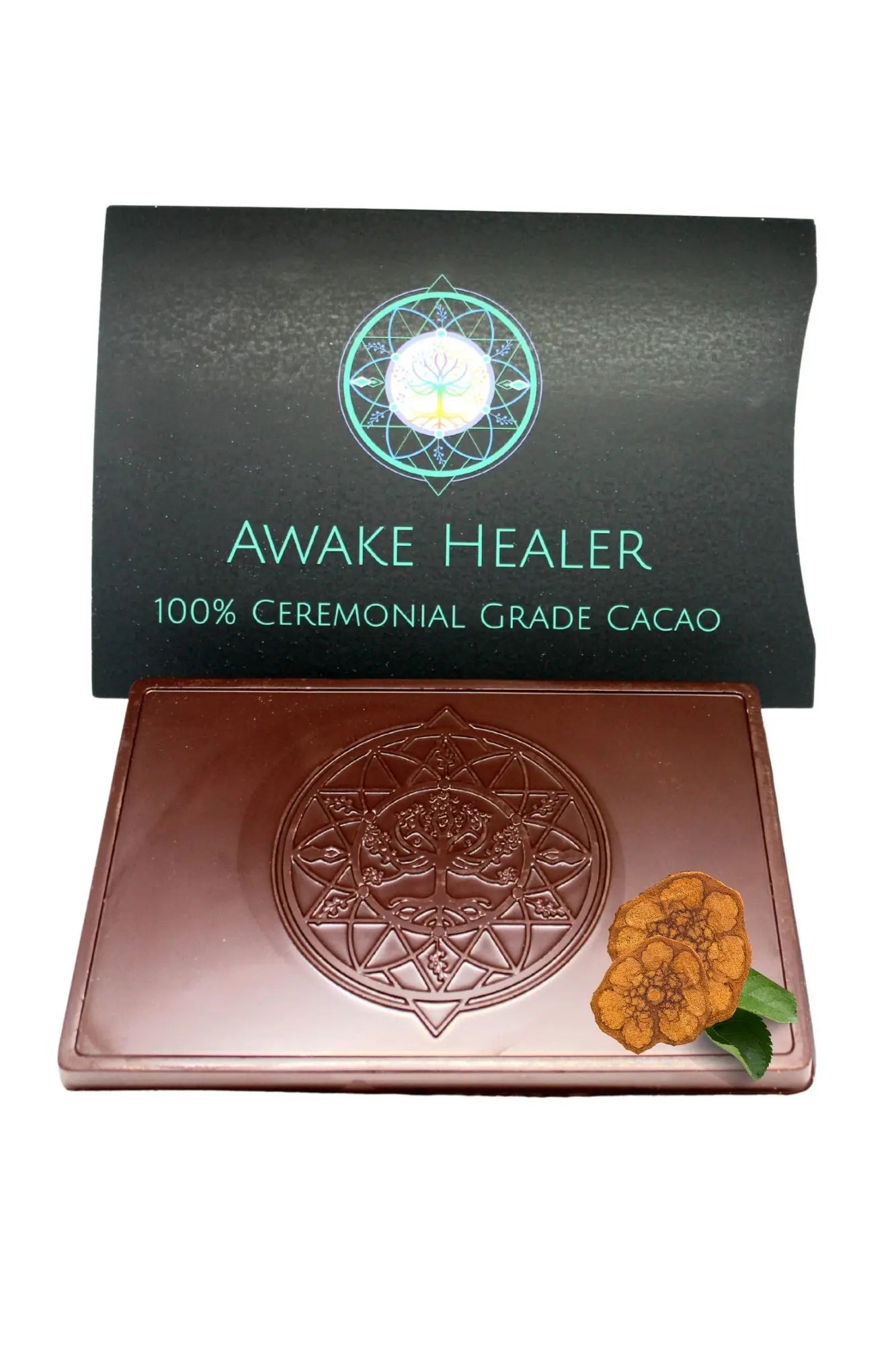

Awake Healer

Ceremonial Cacao - Chocaya™

Ceremonial Cacao - Chocaya™

Couldn't load pickup availability

Awake Healer is dedicated to procuring only the finest plant medicines wherever they may be.

This Cacao, from the Amazon region of Ecuador is a national treasure. The Kichwa tribe in this area has been harvesting the oldest strain of unadulterated cacao in the world. Awake Healer collaborates with a small group of families within the tribe to procure the cacao. They have been caring for these trees the same way their forefathers have for hundreds of years. Awake Healer is dedicated to assisting them in continuing their organic, sustainable, and profitable harvest. It is naturally perfect.

Flavors- Many ceremonial practitioners of Cacao choose to add many natural ingredients when preparing their Cacao. Understanding that it can sometimes be problematic carrying many ingredients, we have experimented with many ingredients, and have found doTERRA essential oils to be easy, and flavorful to use when preparing the cacao. We believe that you will agree!!! It is amazing how such pure, simple ingredients can make such a difference!! The Cinnamon Bark flavor also contains Chile Guajillo...and needs to be tasted to be appreciated!!

Chocaya- As many of you know, Awake Healer has gone through exhaustive efforts to ensure that their plant medicines are the finest in the world. Our Pure Vine (vine-only Ayahuasca) is legal and can be extremely beneficial and powerful in assisting one’s spiritual growth. Combining the Pure Vine with the finest Cacao in the world has helped produce some extraordinary experiences. We only recommend one ounce of Chocaya per serving.

The History of Sacred Cacao

The cacao tree, which is native to the Amazon Basin, was first believed to have been cultivated and used by the Mayo-Chinchipe people as far back as 3300BC. However, it is the Olmecs (1500BC) that are recognised as being the first civilisation to both cultivate and ‘domesticate’ the fruit. Alongside the Aztec and Mayan empires, the cacao plant not only shaped the way that these empires conducted themselves on a day-to-day basis, but also established deep roots in the very beliefs that they upheld.

Originating from the Mayan words Ka’kau, cacao was an intrinsic part of ancient Mayan and Aztec life, not just as a beverage or food, but as a pillar of their economies and an integral part of their religions, appearing in numerous spiritual ceremonies, including death rites and sacrifices. They cultivated the fruit for multiple purposes, even using the cocoa beans as a form of currency.

What is known about the early use of cacao is that it was considered to be sacred and revered by both the Mayan and Aztec people. It was a staple feature in their rituals: used to celebrate new births; required in marriage ceremonies due to its link to fertility (Cacaomama); and even offered up in sacrificial ceremonies to encourage the departed spirits onto the next stage of their journeys.

Consumed primarily in the form of a frothed drink, it was a prized possession and available only to the elite - for it was godly potion that would grant energy and power to those who consumed it (Cacaomama.) For this very reason, it was often featured in many of their rituals, especially those that sought to appease their deities.

In Aztec mythology, there are many tales that demonstrate the people’s belief that man had been created from a combination of maize, cacao, and other plants brought from the “Mountains of Sustenance.” There are numerous depictions of the tree in early Aztec paintings, many of which showcase how the Mesoamericans linked their understanding of divinity and spirituality with cacao (Seawright.)

In Mayan culture, the role of cacao was used alongside blood-letting rituals and sacrificial ceremonies to showcase their strong beliefs that cacao was just as sacred as blood. Often cacao was given to sacrificial victims, often in ways that directly linked chocolate and the sacred body. In fact, the Maya held a yearly festival to honour the cacao god El Chuah, which included several rituals and human sacrifices.

During the annual Aztec ritual in Tenochtitlan, a slave would be chosen to represent Quetzalcoatl. At the end of forty days, during which he had been dressed in finery and given all manner of good food and drink, he was informed of his impending death and then made to dance. If the temple priests saw that he was not dancing as enthusiastically or as well as they expected him to, he was given a drink of itpacalatl, which was a mix of cacao and water used to wash obsidian blades. There were sacrificial blades, and therefore crusted in blood. The sacrifice would be rejuvenated and joyful after drinking this mixture of blood and chocolate, and dance to his death (Coe 103-104.)

Share